prologue

JP

JPFrom now on, I will be talking about samurai.

Wow! Samurai!

I love samurai, they are so cool.

Not just me, I think many people think of samurai when they think of Japan!

You’re right.

But few people know what real samurai were like.

I know what samurai are like in movies, manga, and games, but I don’t know what they were really like.

In fact, even Japanese people don’t know much about it.

Don’t even Japanese know?

The samurai class was established in the 10th century and abolished in the 19th century, so it existed for almost 1,000 years.

Most people, unless they are history buffs, only vaguely remember who represented each century and what they did.

Many people find it difficult to do even that.

I see. So if I watch this series, I’ll know more about samurai than the average Japanese person.

Sure. In this episode, we’ll talk about the origin of the samurai, as the first in a series of samurai episodes.

Origin of samurai

It is said that the samurai originated in the late Heian period (8th to 12th centuries). In this episode, we will discuss two theories about how they were born.

① The theory that local landowners armed themselves to defend their own territory.

② The theory that aristocrats who were in the center of the country were sent to the provinces as military bureaucrats, and that they became rooted in the local area and gained power.

① Local landowners armed themselves to defend their own territory.

During the Heian period (8th to 12th centuries), Japan had a system of “kōchi komin” (the Emperor’s rule over the land and the people).

In other words, all land and people in Japan belonged to the emperor.

Under the kōchi kōmin system, private land ownership was not recognized, so it could not be passed down to the next generation. As a result, the farmers’ motivation was low and tax collection was not successful.

To collect taxes, it is necessary to know the number of citizens in the first place, and a solid household registration system is required. However, people who do not want to pay taxes will find various loopholes, such as not reporting the birth of a child, pretending to be an old person or a woman.

In principle, it is necessary to scrutinize the household registration information, make appropriate corrections, and crack down on non-payment of taxes. However, this requires a large number of bureaucrats. At that time, Japan did not have a system for training enough bureaucrats to operate such an administrative organization, and there was an overwhelming shortage of personnel.

In the end, the imperial court issued the “Kōden Eien Shakaiho” to recognize private land ownership.

This is said to have been more of a post-facto recognition of the situation in which tax collection and land management were not going well and private land ownership had in fact begun to take place, rather than a solution to the problem.

In any case, with the recognition of private land ownership, local influential people with a lot of land appeared in various places. They eventually armed themselves to protect their land, and it is said that the descendants of such people became samurai.

② Central nobles who were sent to remote areas as military bureaucrats became indigenous.

In the Heian period (8th to 12th centuries), the rule of the Yamato court did not extend to all of Japan. In fact, the east of Kanto was a place where the authority of the Yamato court did not reach.

To the east of Kanto lived the Ainu people, who were called “Emishi” at the time. The Yamato court wanted to expand its rule to all of Japan, so it launched a campaign to conquer Emishi.

At the time, the Yamato court had a system of conscription called ritsuryō, in which ordinary farmers were conscripted as soldiers. However, the army, which was mainly composed of farmers with no combat experience, could not defeat the Ainu army, which had a strong cavalry.

Therefore, the Yamato court established a new system called kon’dei, in which professional soldiers were raised. They were paid a salary and trained as professional soldiers.

When they were able to win battles against the Ainu army, they captured many Ainu prisoners. They incorporated the Ainu, who were originally strong warriors, into the Yamato army as soldiers.

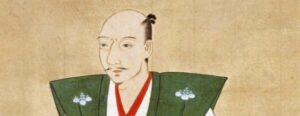

Thus, the Yamato army was able to gain the upper hand in battle. With the help of Sakanoue Tamuramaro, who was appointed as the commander-in-chief of the Emishi conquest, the Yamato court expanded its rule.

By the way, the person who was appointed as the commander-in-chief of the Emishi conquest received the title of Sei-i Taishogun. This title later came to be used to designate the leader of the samurai.

Now, what happened to the Ainu people who were incorporated as combatants?

They were originally enemies, so if they were kept in one place, they would be in trouble if they rebelled.

Therefore, they were dispersed throughout the country.

The places where they were deployed were Kanto, Seto Inland Sea, and Kyushu.

In these places, military bureaucrats were sent from the central government to unite them. The military bureaucrats who were sent there married local leaders and settled down in the area.

In this way, people with a high position in the local area, military power, and connections with the central government appeared. The descendants of these people became samurai.

epilogue

That’s all about the birth of the samurai.

Which theory is more dominant, ① or ②?

It was probably both. Local powerful people wanted a pipeline to the center, and military bureaucrats sent from the center to various parts of the country wanted power in the places where they were sent. The interests of the two parties coincided, and through marriage, they became one.

I see!

It is true that the interests of the local lords and the dispatched military bureaucrats coincide. If they were married and their descendants became samurai, then both ① and ② would be correct.

Next time, we will talk about the Genji and the Heike, who were the leaders of the samurai. With their appearance, the status of the samurai, who were just soldiers, will rise. I hope you look forward to the next episode.

コメント